Sometimes, you don’t know what you know how to do until you see its lack in something else.

I’ve been reading a lot of game materials lately—rulebooks and adventures, but also books on game design principles, advice for world-building, etc… In fact, RPG material is now the bulk of my reading. In among all this material, there’s a different RPG system (not D&D) I’ve been teaching myself that I want to try. I’m looking for a good first adventure to easy myself and my players in. This past week, I’ve gone through several suggested starter adventures and tossed them all aside because of flaws in the way they are constructed. One particular adventure was so egregious that I couldn’t stop thinking about it. It forced me to articulate *why* it didn’t work for me. And that’s when I codified my three design principles.

Now, I’m not going to name the system or the adventure, because I don’t want to call anyone out here and be mean. Instead, I’ll speak in very broad generalities about this adventure’s specific flaws. The adventure began when the players see a mysterious something off in the distance, and the designer assumed they would naturally want to investigate it. You could imagine a castle on a distant hill, if you like (though that’s totally not what it was). However, the designer made learning about it from a distance really hard, with most of the information they could glean hidden behind difficult skill checks (think investigation rolls to notice something or research in a book to uncover history, though that’s totally not what it was). There were so many of these checks in succession, each revealing a different piece of information, that characters very well might be going in blind. Then the designer made getting there really dangerous. As in, deadly dangerous (think having to cross a raging, monster infested river to get to the castle, though that’s totally not what it was). So, there’s a nebulous something, you may not learn anything about it from a distance, and you may die trying to get there. And there’s no narrative reason to go—nobody trapped inside, nobody paying you for a rescue or to take out a big bad. It’s just there, in the distance. You know nothing about it and attempting to reach it may result in a TPK (Total Party Kill). Have at! I don’t know about your players, but I’d put even odds that my players would just say, “Let’s go somewhere else.” I mean, the world is full of mysterious somethings, right? Let’s just keep going and head to the next one. However, the designer accounted for that i the worst way possible. If the characters do decide to leave it alone and go elsewhere, the mysterious something reaches out and grabs them and pulls them in anyway. I read a little further, but at this point I knew that I was done.

I was so put off by this design that a few hours later, I had to explain it to my wife and tell her why it was so egregious (in my humble opinion). And that’s when I articulated three core roleplaying game design principles that I strive for when writing.

Don’t hide important information behind difficult skill checks. And if you do, make sure there is more than one way for the characters to obtain that information. If the adventure relies on the characters learning specific information or solving a specific puzzle, make sure that they either can do so or have multiple alternative ways of acquiring that information. Don’t put your whole scenario behind a single locked door and then make that door near impossible to open. If you do, your adventure grinds to a halt right there. Certainly don’t put your adventure behind several locked doors in succession!

Never assume the players of an adventure will choose the “obvious” course of action. Never ever write, or even think, “the players will want to do X.” Don’t entertain that notion for a moment. I see so many adventures where the designer assumes that their own view of the next logical course of action is so obvious that they aren’t afraid to hook the entire narrative on it. In our current Empire of the Ghouls campaign, the narrative called for the characters to travel clandestinely through several hundred miles of vampire-occupied war-torn territory. Instead, they bought a boat and sailed all the way from the north of that kingdom to its southern most coast. If the adventure design had depended on their encountering something unexpected in that (assumed) overland journey, their unexpected actions would have derailed the adventure right there. Instead, it gave us some fun nautical encounters before we got to our point B.

Make sure your players have agency and the choices they make matter. If the characters are going to ignore your hard to reach castle on the hill and go into the city instead, don’t have something in the city suddenly teleport them inside the castle. Yes, there’s a certain buy-in that good players need to bring to the table in RPGs. The default assumption should be that we’re all adventurers so we don’t shirk adventure. (Don’t be that guy.) But if player choice doesn’t matter, then the game master is just telling themselves a story with the players as proxies. Obviously, some adventures have more latitude than others. An Open Sandbox has more room to veer left and right than a trip down the Yellow Brick Road or a journey through a classic dungeon. But even Dorothy left the Yellow Brick Road a time or two, and that dungeon can offer corridors that terminate in a T with a left and right path. Offer choices and make sure the outcomes matter.

So there you have it. Three principles I try to bring to RPG design. Doesn’t mean that every adventure hits it 100% every time, or that there isn’t room in here for interpretation. But these are overarching goals I try to keep front and center both when writing and evaluating roleplaying game adventures.

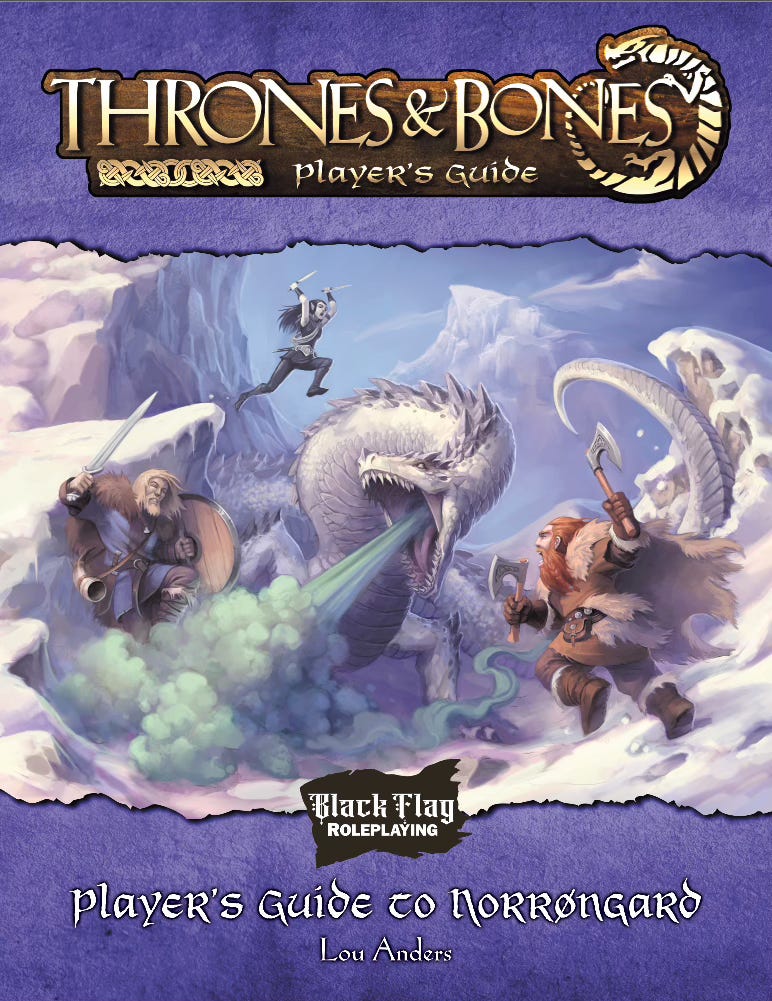

And now, as a thank you for staying with me, here are sneak peaks of two upcoming projects that will debut from Lazy Wolf Studios this summer:

Of course, players might also be conditioned to explore every Ruin and mysterious mountain. I remember in one of my sessions, placing a ghost pirate ship just at the horizon, to foreshadow a later encounter. The players had no boat, they didn’t know what was in the ship, but upon my soul if they didn’t steal a çanoe and paddle out to sea. I had to invent a whole bunch of monsters and encounters on the fly

Something might be said here about the negative effect of video games on pen and paper RPG’s. In a video game, the mere Presence of Something Mysterious is enough reason to explore, because you’re already immersed in the world, you already know the rules of the game: explore and get rewarded. I don’t know if the promise of a reward is the driving factor in playing a TTRPG