When I first started learning how to write, I did an exercise that was truly invaluable. I would pick a movie, sit down with my laptop in my lap and the remote by my side, and I would watch it and write down every single beat.

A beat is a moment, a thing that happens, an instant of story. So if a detective smashes a window, falls awkwardly over the sill into the room, and, when rising, is attacked from behind by a gorilla (why not?), that’s three beats.

And I’d pause constantly (this could make watching the movie take all afternoon), and I’d write down the time. When I got to the end of the film, the moment when the curtain came down, before the credits roll, I’d note the actual length of the film (not the runtime, which includes the credits).

Then I’d go back and I’d note when big things happened, paying particular attention to the one-quarter mark, the midpoint, and the three-quarters mark.

Over time this taught me so much about structure, and over a longer time, I internalized it.

I’ve since added a stage to this exercise.

After I’ve broken down the film in this way, I go through all the beats and I create an outline of the film. Just the major events. Our example of the three beats and what followed them above might be written as “detective goes to office /fight/gets clue.” And in this way, I’d generate an outline of the narrative.

Then I’d distill it further. “Protagonist fights minor bad guy, rewarded with clue.”

I’d end up with a minimal outline, without any characters or setting. Just “protagonist” and “antagonist” and “good guys’ headquarters” and “crowded pedestrian area” etc…

And that gave me the heart of the narrative. And when you have that, you can build up something new from there. And that brings us around to…

In my previous post, I talked about how the 2015 Ant-Man film brilliantly borrowed, not the theme or the setting or the tone, but the structure of a popular late 90s science fiction film.

To figure out which film I’m talking about, let’s distill Ant-Man down. I’ll break my rule and leave a couple tiny bits of setting in too, because they carry over.

Protagonist: Young criminal who’s life is going nowhere. Gets in trouble.

Helped by older guy. Given chance to be something bigger.

Rejects chance. Gets in trouble again with authorities.

Sprung by older guy.

Protagonist is taken to a three-story Victorian house.

Shown into secret room with a computer terminal full of computers screens.

Told I’ve had my eye on you a long time. Only you can do the thing.

Then a black clad tough woman with a severe haircut has to teach protagonist how to fight.

Woman resents protagonist, and doesn’t think the old guy’s faith in protagonist is correct.

Old guy tells protagonist “the one thing you should never do is…”

Protagonist assaults a high security complex with a team of criminals.

Protagonist does the one thing they’re never supposed to do.

Protagonist see the underlying nature of reality. Beats bad guy.

Protagonist comes back and kisses the tough woman.

You know what it is, right? A couple of the beats shift around, but I’m sure you spotted it. It’s The Matrix, of course.

Ant-Man has nothing to do with virtual reality, artificial intelligence, cyberpunk, illusion verses reality—all the things other films copied like crazy in the years following The Matrix. No, the filmmakers of Ant-Man ignored all that and took what really worked—the structure. And on that structure, they build a completely different, very original, and in my opinion, great film.

And if you aren’t convinced, let me point out two things:

The Matrix Reloaded features an extended highway chase in which our heroes fight a pair of weird albino twins who can disappear and reappear over short distances. Ant-Man and the Wasp features an extended highway chase and an antagonist who dresses in white and can phase. Oh, and it also features Morpheus himself, Laurence Fishburne.

The Matrix Revolutions features an army liberating an underground city and an antagonist who can exert control over reality. Quantumania features an army liberating a (sub-material, ie “underground”) city and an antagonist who can exert control over reality.

Gee?

And let me stress—NONE OF THIS IS BAD. Bad is when someone writes a story, and you say, “I’m going to write the same story!” None of the Ant-Man films have anything to do with the narrative of the Matrix films. They are their own films, with their own themes and their own tones, but they took good lessons from the structure. And they made their own gold with it.

Since it was recently back in theaters, maybe I should talk about Return of the Jedi next time and where it got its structure (and sadly also some of its characters and setting.) And also how it’s actually got more acts than a three act structure permits.

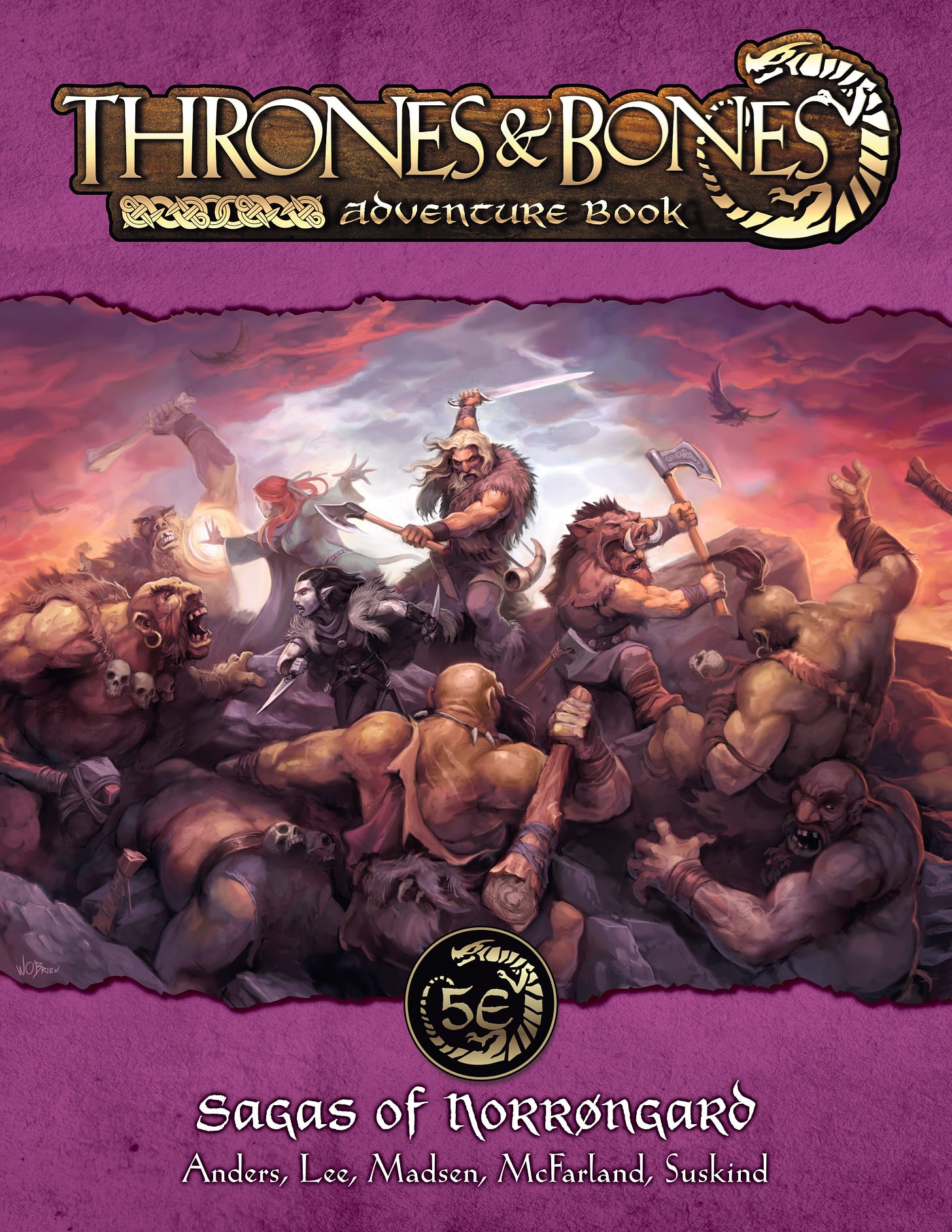

Meanwhile, thanks for reading. Those of you who are here for the tabletop roleplaying content and not writing advice, I want to reward you for hanging around! From now until May 10th, you can follow the link here to get 50% off the PDF of Sagas of Norrøngard. Sagas of Norrøngard is an adventure book that contains seven adventures designed for character levels 3 through 8. It’s written by myself and designers Jeff Lee, Sarah Madsen, Ben McFarland, and Brian Suskind. It’s also designed to follow the two adventures in the core book, Thrones & Bones: Norrøngard, to make a complete 1st to 8th level campaign. The book is usually $24.99 in PDF, but you can get it for $12.50 for the next week. And that’s it for now. Thanks for reading!

I didn't get it until I read the beats a second time. And there it is. That's fantastic. I might have to try that exercise. Thank you, Lou